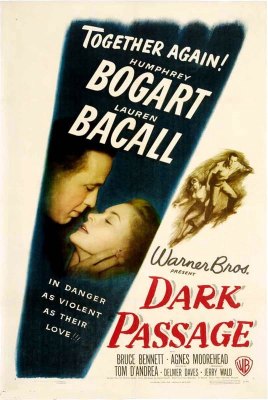

Bogie & Bacall: One of Hollywood’s most well-known and beloved couples, on screen and off. After meeting on the set of To Have and Have Not, Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart married in 1945 and went on to make three more films together.

I enjoy all four of the Bogie & Bacall films, but tend to re-watch The Big Sleep more than the others. When I saw that a blogathon dedicated to the year 1947 had been announced, I decided to give Dark Passage another look, since it was released in that year. I’ve seen the film two or three times before, compared to at least 15 re-watches of The Big Sleep!

Dark Passage tells the story of Vincent Parry (Bogart), a man who has been convicted of murdering his wife. He cleverly escapes from San Quentin, hiding in the back of a garbage truck, and goes on the lam.

Vincent meets Irene Jansen (Bacall), who offers to help him. She’s been following his trial and believes he’s innocent. Her father, who died in prison, was also wrongfully convicted, which drives her dedication to Vincent’s cause.

Dark Passage was directed by Delmer Daves. Daves also re-wrote the screenplay, originally drafted by David Goodis, who wrote the film’s source novel.

This is an unconventional film noir, and after watching it again for this blogathon, I appreciate it more than ever. I’d even say that it has taken its rightful spot as my second favorite Bogart/Bacall film!

We begin the film in Vincent’s perspective, never seeing his face — instead, seeing through his eyes. We see the suspicious eyes of the stranger from whom he hitches a ride, surveying Vincent as an announcement about the escaped prisoner plays on the radio. We see Irene through Vincent’s eyes, when she stops by the side of the road and meets him for the first time. We see the hand of a police officer, inching toward Vincent’s own hand as he hides beneath a blanket in Irene’s car.

While this wasn’t the first film to put the viewer directly into the perspective of the central character, the technique is used with great success here, building a mountain of tension as Vincent attempts to evade capture with Irene’s help. He’s at first suspicious of Irene, and anxious that he’ll be found out or get in her way, which only adds to the mood of the film.

Vincent eventually gets plastic surgery and changes his name in hopes of securing his freedom permanently, and it isn’t until he wakes from surgery (about 40 minutes into the film) that we finally see Bogart’s face (at first swathed in bandages) and get a slightly more omniscient perspective. Prior to the surgery, even when Vincent is shown from the front (such as in the cab scene, pictured above), his face is obscured or completely hidden in shadow.

The transition between the subjective POV and Vincent’s post-surgery life brings one of the film’s most striking scenes, a surreal nightmare-like sequence in which Vincent sees Irene, Madge, the surgeon, and the driver that he hitched a ride from — usually as though filtered through a kaleidoscope.

Bogart and Bacall both give wonderful performances in this film. Bogart is a rough-edged man, but a sincere one. While he has a violent streak (as proven by the way he socks the driver who picks him up just after his escape), the audience believes that he’s innocent in his wife’s death. Bacall is calm, cool, collected, and determined to do anything she can to help Vincent avoid the same outcome as her father — an admirable-but-guarded character, until her growing affection for Vincent leads her to let down her guard a bit.

Stealing a number of scenes is Agnes Moorehead as Madge, the woman who testified against Vincent at his trial. She’s a nosy, stubborn, and scheming woman, with a strong personality… and a lot of anxiety over Vincent’s prison escape (or so it seems). Having become acquainted with Irene while Vincent was in prison, her presence becomes inescapable to him after his escape. Moorehead pulls the character off exceedingly well, especially in her fiery confrontation scene with Bogart near the film’s end.

Story-wise, this film doesn’t have much to set it apart from other noir films. It’s a tale of wrongful conviction, running from the law, and unraveling a complex web of lies/murder — nothing out of the ordinary for the genre. But with such a great cast, nice photography, and interesting little twists (like the surgical element of Vincent’s escape, and the use of subjective POV), Dark Passage is a fantastic watch. 1947 was a big year of the genre, with other greats such as Nightmare Alley and Out of the Past released, but Dark Passage can certainly be counted as one of the best and most memorable screen stories of the year.

Visit Shadows & Satin or Speakeasy, the blogathon’s two wonderful hosts, for more fascinating reviews and features on films from 1947!

I remember this flick and being really surprised at how good the whole POV elements were used in the first half of the movies. I like Bogart and Bacall in this but not their best collaberation

LikeLike

Which is your favorite of their films? I always feel like I’m in the minority ranking The Big Sleep as their best; a lot of people think it’s over-complicated.

LikeLike

Great selection, Lindsey — I, too, appreciate this film more every time I see it. I agree that Bogart turned in a memorable performance, and Agnes Moorehead is simply outstanding. I like this film better than the other Camera-I movie (that I know of), Lady in the Lake, not least of which because the point of view does change and you get to see the protagonist for the remainder of the film. Thanks so much for this pick, and for contributing to the blogathon!

LikeLike

I haven’t seen Lady in the Lake, but I’m interested to now that you mention it, as I see that Robert Montgomery directed it! I’ve never watched any of his directorial efforts, so I’ll have to seek that one out (even if it isn’t quite as successful as Dark Passage in using the POV trick).

Thank you for co-hosting this wonderful event! I’m going to spend my morning catching up on everyone else’s posts!

LikeLike

I love that still you posted of Agnes Moorhead giving Bogart the death stare. She was fabulous in this film but so was everyone else.

I admire the novelty and planning it took to shoot part of the film from Bogart’s POV. I know it’s not to everyone’s taste, but it’s a refreshing twist on storytelling. Great choice for the blogathon!

LikeLike

That confrontation scene is SO good. And I agree regarding the POV — I can see why not everyone likes it, but it really sets the film apart and is used much more successfully here than it has been in other films.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am a big admire of Bogart, but I always thought Moorehead’s performance stole the film. It is a film that grows on you. And there are great scenes of San Francisco.

LikeLike

Yes, the city’s almost a character of its own in this film! I was glad to discover that the beautiful art deco building used for Irene’s apartment is still standing and has been preserved — glass-block elevator and all.

LikeLike

I’ve never made it all the way through this film – it’s certainly not my favourite Bogart/Bacall partnership – but as you and another blogger have reviewed it so favourably I think it’s time for another watch! Third time lucky…?!

LikeLike

Sorry to hear that! Don’t let us overhype it for you, haha. Go in with low expectations since you’ve never been able to finish it before. Hopefully you will enjoy it this time around, but if you don’t, that’s fine too — we all have different taste!

LikeLike

This is a transitional film in a couple of ways. The familiar Warner Bros stock company of character actors is gone, giving it a more docu feel. I’ve always felt that Bogart spends so much time bandaged not just so Daves can show off his mastery of POV, but also to ease the audience into his aged appearance opposite his child bride. His surgeon even says his new face will make him look older. Unsurprisingly, Goodis later sued tv’s The Fugitive.

LikeLike

Interesting thought re: the aging of the character. Their age difference is so rarely talked about among today’s classic film fans; I always assumed it wasn’t a problem with their contemporary audiences. I’ll have to do some research and see if it was ever mentioned in the fan mags or reviews of their films. Thanks for the comment!

LikeLike

I don’t think it ever a factor for the fans, as she seemed a perfect match for him. But he had some miles on him since Big Sleep, and the disparity more pronounced. Why else would they include the “look older” line, normally a no-no applied to a leading man?

LikeLike

This is the one Bogie/Bacall I haven’t seen, and like you, I could watch The Big Sleep anytime. Will have to give this a look. 1947 truly was a great year for noir!

LikeLike

Hope you enjoy it when you get around to watching it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I like this one too, I know it’s not perfect but I like what they did with the premise and LOVE Agnes’ work in it. Thanks so much for taking part.

LikeLike

It’s great to see that so many people appreciate Agnes’ performance! And you’re very welcome, thanks for co-hosing such a great event!

LikeLike

I always enjoy this movie. It can be a real nail-biter at times. I’m glad to see other commenters like it–I feel like a lot of times people dismiss Dark Passage, which is very unfair. My favorite part is the ending. Very romantic!

LikeLike